*Available directly from our distributors, click the Available On tab below

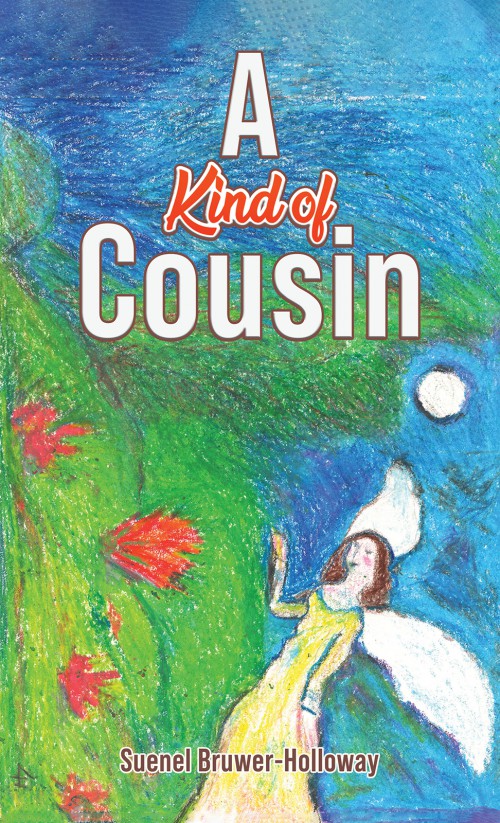

Suenel Brewer-Holloway’s collection of short stories, recently published by Austin Macaulay, is a kaleidoscopic picture of South African culture, particularly the wine culture of the Cape. Captured with what feels like a dolly from a film set, the author shows the relentless and relentlessly destructive hand of wine across a group of people brought together by the production of one of the world’s most seductive products. For those who have lived within the vicinity of this strange and seductive dominance or known its history and the desperation of its hidden victims (babies born with Alcohol Dependence Syndrome of drinking mothers, for instance) there are still surprises shown through the careful telling of so many and so widely varied truths. Bruwer-Holloway often makes the re-reading of sentences a necessity, her style disarmingly matter-of-fact about some of the most terrible discrepancies of human history. I like this author’s style - it is perfect for its subject – the grasping of an inchoate miasma of despair hiding in its echo field – one couched in and surrounded by the glamour of a product delightful in measure and desperate in the often-tragic consequences of its over-partaking. It is not simply that some people get drunk when they drink, but rather that workers in the vineyards were partly paid – and are still so paid today – in wine. Thus, a social and pleasant beverage became, historically, an easy and destructive means to suffering, even and especially death. The perpetuation of these horrors can be seen in these stories through the grim effects on the children whose impoverished parents have become almost accidentally involved with the liberality of its consumption. No one who lives outside the winelands can know the complexity of the clouds. Bruwer-Holloway calls out the complexities of a culture whose own language is itself one of the newest in the world. Euphemistically termed kitchen Dutch, Afrikaans (now become a noun to replace the word Afrikaner) provides a richly fecund container to identity, and the book, like a stretched-out documentary filmed from the wings of its subjects’ lives, paints the huge and hugely hidden wounds of a hidden society as if they were grazes.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience and for marketing purposes.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies